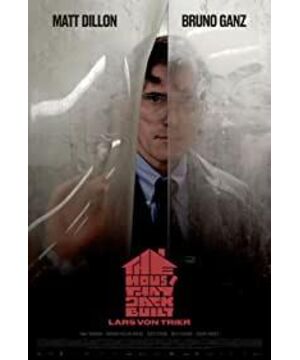

If the so-called "evil" is just a value judgment, that is, if it is bad only in the eyes of people who don't like it, but in the eyes of people who already have the quality of "evil", it is on the contrary. Of course, where does this assumption lead us? It is on this relativism that Lars von Trier develops his defense of what we usually call "evil". If we regard such aspects as conceited, vulgar, rude, impulsive, narcissistic, irrational, controlling, moody, etc. as objective existence, and do not presume an emotional color for them, then we have all The individual of these qualities is just a result of the chain of causality, and his actions because of these qualities (that is, his nature) are taken for granted. Listen to Matt Dillon's defense and you'll see what I'm talking about. Try to imagine that Matt Dillon's image is not just a person, but a symbol of an entire civilization: those qualities that trigger a series of killings in the individual, and the effect of the totalitarian war and massacre in the group. Extinction. Ego is an abstract quality, while extinction is a fact, they are not the same, so to connect ego and extinction requires a transformation process from the virtual to the real, like building a house, or calling it social construction Also can. In the process of using such a material to construct such a society, art, or "noble rot", has become another excuse for self-defense. But after all, this is what Lars von Trier takes for granted, and it doesn't take into account the feelings of the people he uses to construct his art. It's like Matt Dillon's pervert doesn't feel how his victims feel. Usually, social builders do not consider the feelings of the social constituents, and we say that this is a bad society. If something like the Holocaust happens to an extreme, then this is a bad society. But in Lars von Trier's eyes, this is a natural phenomenon of "one-shot success", and the reason why we have such results is because human beings are such a kind of existence - evil is human beings of course. Rebuttal to this: 1. This is the director's own values, the personal color is too strong, not everyone has all the characteristics of perversion, so other people's things are of course different from his, or evil is not a matter of course for everyone ;2. This is the fallacy of relativism, because abstract good and evil are absolute, and they are embodied in specific events, so the real evil people and evil things are absolutely "bad", and cannot be said to be in any case. It is taken for granted; 3. Even if we accept the relativity of evil, we cannot accept evil deeds. After all, the former exists only in logic, while the latter has practical consequences. The film's display of violence can cause physical discomfort, so it is not recommended.

Supplement:

In Zizek's little book "The Incident", there is a commentary on the straightforward display of torture in movies, which I think is appropriate here. The only thing to do is to replace Catherine Bigelow with Lars von Trier, and torture with evil:

In a letter to the Los Angeles Times, the director of the film "Hunting Bin Laden", Kathryn Bigelow, defended the realistic torture scenes in the film. It was through torture and other means that American agents obtained information about the • Bin Laden Intelligence, Bigelow wrote in the letter: "We all know that description is not equal to approval. If this were not the case, then no painter would dare to paint inhumane scenes, and no writer would dare to write about inhumanity, And no director dares to shoot such tricky subjects that reflect our time." However, is this really the case? Even given the unprecedented urgency of the realities of the fight against terrorism, and even if we let go of abstract moralist stances, is there no reason to think that because human abuse is so deeply destructive, even a neutral description of it itself (also i.e. an attempt to neutralize its destructive practices) already constitutes some degree of approval? (P194.) The dirtiest defense of the film is to argue: Bigelow here avoids cheap pan-moralization, she reflects the reality of the fight against terror in a sober way, and the film raises difficult questions and prompts us to think (Also, as some critics say, she "deconstructs" the feminist cliché - Maya displays neither sexual interest nor sentimental traits, she is as strong and committed as a man ). Our answer to this is that it is precisely when confronted with a subject such as torture that we should not "think too much". Take rape as an analogy: if a film presented a violent rape scene with the same neutral indifference and claimed that we should avoid cheap pan-moralization and think about the intricacies of rape, you would What do you think? A deep intuition tells us that there is a serious mistake here: I would rather live in a society where rape is absolutely unacceptable, in which anyone who advocates rape is considered a hopeless fool; In a society that allows rape to be justified - so is torture: in fact, one of the hallmarks of moral progress is precisely this non-discussing, "dogmatic" resistance to torture. (P198.) Will torture save lives? Maybe, but it must kill the conscience—and the filthiest defense is this: the true hero renounces his conscience to save the lives of his fellow men. The normalization of torture in The Hunt for Bin Laden heralds a moral vacuum that is closing in on us. (P199.)

View more about The House That Jack Built reviews