The gaze lens in "Portrait of a Burning Woman" has a large visual weight. The gaze witnesses the emotional surging of the characters. The subject-object relationship between the gazes is also in the creation of the portrait in the film. In addition, the gaze is also a female gaze. The carrier of women's emotions and desires.

The film places the narrative situation in an ancient castle on an isolated island, and men are at the absolute edge. By constructing a utopian female community, the film isolates the male gaze and the corresponding viewing pleasure, thereby establishing a unique female writing.

Gaze and Seeing: The Erosive Gaze

"Portrait of a Burning Woman" is almost a movie with eyes connected in series. The eyes are linked to the portrait, the eyes fuel the burning of emotions, and the eyes also penetrate the same-sex taboo in the age of ritual restraint. These eye shots seem to gather energy, constantly pushing the flow of the film.

Marian, a young female painter, came to the isolated island to paint a portrait of the down and down noble lady Eloise. Marianne was assigned to observe Eloise secretly, to paint her portrait and send it to the man's family far away. When Marianne first saw Eloise, Eloise was wearing a cloak robe and only showed her back. Marianne's eyes crossed the stairs and fell ghostly on Eloise. The cross-cut footage of the back and the gaze, with an undertone of observation and peeping, Marian notes the parts of Eloise's body, profile, lips, pinna and hands.

These are the gaze of the painter when he observes before painting, and finally translated into the brushstrokes of the portrait. At the beach, Marianne's gaze fell directly on Eloise's hand, and then turned into the outline of a hand on the paper. Initially, these observational and scrutinizing glances were combined with the creation of portraiture, and Heloiz also gave a response to the gaze. The lens stayed for a long time, and it was a suspicious look.

It was in the constant eye contact that Marianne and Heloiz confirmed their mutual affection, and the ambiguous flow began to flow in their eyes. One day, Marianne and Eloise were sitting at the piano, and Marianne played a piece of Vivaldi's "Four Seasons" for her. At this time, Eloise's eyes were full of affection. In this piano passage, the gaze is completely preserved, and even a little indulged for a long time. Modern movies seem to have no so much patience for the gaze of the eyes. Modern society is full of speed, and the gaze is only for a moment. But we know that "when falling in love, the eyes of the person you love are attentive and full of affection. At this moment, even if there are thousands of words, hugging each other, it is difficult to let go of love, only lingering, can you approach this feeling ." "Portrait of a Lady on Fire" is a journey of gaze, transitioning from the gaze of a painter to that of love.

Because of the gaze of love, there is also the debate about portraiture that follows. A painter's viewing can consist of the traces he smears on the canvas or paper. Apparently, Eloise was dissatisfied with the portrait that Marianne had smuggled into, believing it had no life and no sense of existence. Marianne explained that portraiture also has rules, conventions and common ideas, and that existence is only fleeting and may lack authenticity. Heloiz retorted angrily, some emotions will not be fleeting, and Marianne, as a painter, is too far away from her works.

It is necessary for us to talk about the aesthetics of portraiture, as mentioned in the French philosopher Luc Nancy's book "The Gaze of Portraiture": "The business of painting is not the representation of a subject: it is every time a subjectivity or as it is. The execution of self-existence.” That is to say, the portrait in the eyes of Heloiz invites us to gaze at some kind of soul that appears in or on the image, whether this soul can also be understood as a love?

Director Sima An also tried to subvert and dissolve the hidden power relationship between the painter and the model. There is a subtle power relationship between painting and being painted, staring and being stared at, between painter and model. Eloise tends to think that she and Marianne are equal in the process of painting, that she is looking at the painter when she is being watched, and that gaze should be fluid and equal.

John Berger discusses the act of seeing in The Way of Seeing, when he says, "We don't just look at one thing; Makes us believe that we are in the world that can be seen." Seeing and being seen are two sides of the same world, and the game where two people exchange positions and sights due to the inequality of power is actually on the level of love. Extend the fight.

Regarding the power and will of love, Han Bingzhe has a wonderful discussion in "Death of Eros", love is first of all de-narcissistic, "both parties in love must first come out of self, enter each other, let self To die in the other side can be reborn... Love is a pas de deux, it breaks one person's perspective and allows the world to be reborn from the perspective of the other, from elsewhere." This is a very interesting retrospective behavior, in watching and retrospecting, power is going on With the reconfiguration, eroticism also slanted out.

Utopian narrative and women's community

The narrative space of "Portrait of a Burning Woman" is placed on an isolated island in Brittany. There are only four female characters, and the male characters in the whole film either exist only in the characters' discourses, or they are functionally brushed out. It seems that men are in an absolute marginal position. , but even so, the absence of men is present everywhere, such as the maid's pregnancy and abortion, the absent father, and the presence of the fetus in pregnancy; in addition, the patriarchal society, as the presence of absence, has always shrouded this family on the isolated island. Due to the decline of the family, Heloiz had to marry a wealthy businessman in Milan, Italy, while Heloiz's sister failed to resist marriage and committed suicide by jumping off a cliff. Heloiz could only succumb to his own destiny.

Under the shadow of patriarchy, Simaan tried to construct a female community. The three women, the maid, the painter, and the young lady, live together, with equal personalities, and the class seems to be erased. There is a shot, the camera is looking straight, the maid is embroidering, the lady is cutting vegetables, and the painter Marianne, who is a guest, sits down in the middle. In this scene, it seems that class and identity are replaced or flattened to fill. And Eloise and Marianne secretly fell in love, and finally lingered and burned. These same-sex emotions were even more taboo in the era of ritual restraint at that time. Simaan tries to re-enact reality in a very utopian narrative experiment, and declares women's independence, equality and resistance.

But also because of this, the same-sex elements are placed in a utopian narrative, and the overhead of social attributes will inevitably flow into conceptualization. This is a decidedly different line of thought from Carol or The Life of Adele. Because the latter all have a very real social background, complex interpersonal relationships, and many prejudices and age limitations of gender power are implied. Therefore, the kind of homosexuality that breaks through prejudice and shackles is particularly moving.

The Anti-Gaze: Female Subjectivity

At the end of the film there is an interesting look at each other, where Eloise complains that only Marianne can paint, and it's someone else who paints. Marianne then brought a round mirror, the mirror leaned against Eloise's lower body, reflecting Marianne's face, Marianne painted her body on Eloise's book, and gave it to Eloise as a memorial. Looking at each other this time, it penetrates the female body, which interweaves lust and love, and reiterates the equality between love.

An interesting point we noticed is that there are several interesting erotic scenes in the film. Tobacco is applied to the armpit hair and the fingers are drawn back and forth under the armpit, which is undoubtedly a presumed sexual intercourse. "Hair is about sexuality and passion. Only by weakening a woman's sexual passion can the viewer feel that he owns this passion." Tobacco smeared on armpit hair brings imaginary sexual arousal, compared to direct and bold sex scenes, This implicit and symbolic sex scene is undoubtedly an image metaphor for the restrained style of the film: on the one hand, it avoids the male gaze, and on the other hand, it seeks to write another female desire. It avoids being criticized as a substitute for the male gaze and desire to see, and as an erotic curiosity.

The display of the female body has always been used as a visual spectacle directly appealing to the male group, and this phenomenon has been criticized and resisted by feminists. In Laura Mulvey's classic essay "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Film", "In a world arranged by sexual imbalances, the pleasure of seeing is divided into active/male and passive/female. The eye of the decisive man projects his fantasies onto the female form stylized as such. Women are seen and shown at the same time in their traditional exhibitionist roles, their appearance coded into intense visual hull erotic appeal, so that they can be said to have the connotation of being seen.”

Han Bingzhe's "Death of Eros" has commented on pornography. He believes that "only love can add a sense of ritual to erotic desire or sex, not to display it." With a sense of ritual, after all, the direct display of sex is hardly the result of a male gaze.

Ximaan's creative interpretation of gaze/watching/gazing indicates the existence of female subjectivity, and is also a demand for resistance and equality.

Literary Intertextual Structure

"Portrait of a Burning Woman" is not content with a straightforward narrative of a love affair, but constructs a sufficiently sophisticated intertextual structure at the textual level. In the middle of the film, Eloise, Marianne, and the maid Sophie read at the table on the eve of the night, and Eloise reads the clip of Orpheus going to Hades to save his wife Eurydice in the book.

This text comes from the Metamorphoses by the Roman poet Ovid:

He was worried that she wouldn't be able to keep up, eager to take a look, couldn't help but

Looking back, she fell into the abyss again at this moment.

He hurriedly stretched out his arms to embrace his wife,

But this unfortunate only clings to the backward airflow.

And once again, she was seized by death, to her husband

No complaints (what are you complaining about? Unless you love her too much?)

She only spit out the last "goodbye", not knowing her husband

Whether she could hear it, she fell back to where she started.

Orpheus and Eurydice are a classic ancient Greek mythology. According to legend, Orpheus had profound musical attainments and was proficient in the lyre. Unfortunately, his new wife Eurydice was killed by a poisonous snake. Orpheus was distraught and broke through many obstacles to come to the underworld, begging Hades to let his wife return to the world. Orpheus swayed the strings lightly and moved the queen of Hades with the sobbing music. They allowed Orpheus to bring his wife back to the world, but demanded that he must walk in front of his wife, and he could not look back at her or talk to her before leaving the underworld, or he would lose her forever. After thanking Pluto and Pluto, the amnesty couple hurriedly set foot on the road back to the underworld. When approaching the sun, Orpheus suddenly felt that the footsteps following him disappeared. He suspected that his wife was not following, and in a hurry, he forgot all the instructions from the underworld, and hurriedly turned around, trying to find his wife. When he turned around, he didn't even have time to see his wife's shadow, and she passed away from his eyes.

In the film, the three talk about why Orpheus turned back. The maid felt very angry and complained about Orpheus' cowardice. Marian thought that Orpheus chose her in his memory when he turned back. This was not a lover's choice, but a poet's choice. Heloise thought that perhaps Eurydice had called her "turn around" to turn her husband back.

In the previous interpretations of this Greek myth, we only saw the psychological and emotional path of Orpheus, how he was deeply affectionate and how he bravely ventured into the underworld to find his lover. But we never know what Eurydice thought. Was she willing to return to the earth? Is she still her after the resurrection? Heloiz's interpretation is from the perspective of the female subject, showing the resistance of female consciousness and the demand for equality in love.

This myth has a subtle counterpoint relationship with the film's plot, implying the rare and consistent emotional ending between Heloiz and Marianne. They cannot resist the shackles imposed by the times, whether it is arranged marriages under patriarchy, or homosexual love that is not morally allowed under the domination of heterosexuality. When Marianne finished painting the portrait and was about to leave herself and step out of the castle gate, Eloise affectionately shouted "Turn around". Marianne turned her head, the light disappeared immediately, and Eloise, who was wearing a white wedding dress, was swept away by darkness.

The end of the film is that many years later, Marianne took her own works to the art exhibition in the museum. The director borrowed an audience to point out Marianne's "Orpheus and Eurydice", and the traditional painting Lieutenant Orpheus. The freeze frame was different before turning, and Orpheus of Marianne turned and confronted Eurydice, as if they were saying goodbye. This is a sad and helpless farewell. In an era when women's consciousness is powerless to break through the shackles of etiquette, falling in love means farewell and endless regrets.

Marianne saw the portrait of Eloise at the exhibition again. Her fingers were tucked in a book, revealing the page number 28, and that page contained their love memories. The confirmation of the memory of her lover's love complicates Marianne's emotions. Undoubtedly this is the poet's choice, they choose to stay in each other's memory. Cleverly, Heloise in the portrait is dressed in white, and Marianne in front of the portrait is dressed in blue, which corresponds to the oil painting of Orpheus and Eurydice, but this time, his eyes are not in the underworld and the sun. , and flows quietly between the people in the painting and those outside the painting.

Simaan inserted a classical Greek myth into the narrative, forming an ingenious intertextual structure with the fate of the characters, and through the interpretation and rewriting of the classical myths of Orpheus and Eurydice, the text emphasizes harmony. Reaffirms a sense of femininity. This is the subtlety of Simaan women's writing.

Epilogue

"Portrait of a Burning Woman" is a very unique and delicate female writing. Through an overhead utopian narrative experiment, it isolates and evades the male gaze, and provides reasonable motivation for the female gaze through the action of art and literature on watching. Construct a gay erotic journey around the gaze. The embedded mythology not only expands the emotional space of the story, excavates the unique life and emotional experience of women, but also has profound gender reflection, reiterates the issue of female desire and subjectivity, and is full of idealism.

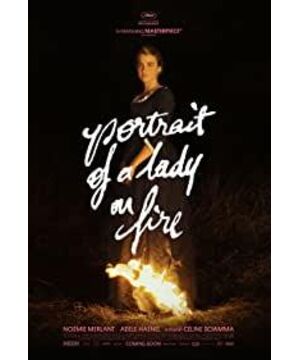

View more about Portrait of a Lady on Fire reviews