Unusually for a first film, the strangely titled opus feels more like a summation work, such as “8½” or especially “All That Jazz,” as it centers on an artist who battles creeping infirmity and deathly portents by plunging into a grandiose project. On the most superficial level, many viewers will be nauseated by the many explicit manifestations of physical malfunction, bodily fluids, bleeding and deterioration. A larger issue will be the film's developing spin into realms that can most charitably be described as ambiguous and more derisively as obscurantist and incomprehensible.

At the same time, the picture exerts sufficient power and artistic mystery to pull the willing a fair way down its twisty trail, and a first-rate cast led by Philip Seymour Hoffman and some wonderful women provide a constant lifeline even when it's hard to know what's going on.

For such serious and accomplished artists, Caden Cotard (Hoffman) and Adele Lack (Catherine Keener) live in surprisingly mundane and physically cramped circumstances in upstate Schenectady, NY Caden, who directs a local theater company, and Adele, an adventurous painter, co-exist in a marginal way but seem mentally and emotionally preoccupied, an impression confirmed when Adele tells Caden to stay home while she and their little daughter fly off to Berlin, where she's having a major gallery opening.

Even before her departure, Caden has begun suffering from a litany of physical maladies as well as the realization that his direction of others' plays doesn't allow him room for personal expression. At least Adele's trip would seem to open the door to Caden's consummation of a strong attraction between him and comely box office worker Hazel (a curly-red-haired Samantha Morton), who, in one early indication of oddities to come, purchases and soon occupies a house that's burning and full of smoke.

After Caden's disabilities worsen and things go awry with Hazel, the action explicitly jumps ahead to 2009, when he wins a MacArthur grant and decides to undertake a theatrical venture in which an increasingly massive number of players will act, or re-enact, life as Caden sees it in a freshly constructed replica of Manhattan under the big top of an enormous warehouse.

Yarn's multiple layers begin manifesting themselves at this stage. It would be folly to pretend that someone watching it all for the first time could enumerate, or even keep track of, every strand of Kaufman's doubling process, or make entirely coherent sense out of the life -versus-art, life-as-art, or art-instead-of-life postulations that come into play in the second half. Viewers' reactions will depend on how far they're able to go with the writer-director before either giving up or giving in to his neurotic flights of fancy.

Without revealing too much, it can be said that Caden eventually casts an oddball actor (Tom Noonan), who's tall and thin rather than squat, to play himself in the evolving epic, and, to play Hazel, chooses an actress (Emily Watson) who's a near-lookalike. Emotional lines become crossed among these four, with both agreeable and dire results, but a throughline of worry, despair, loneliness and overriding unhappiness is provided by Caden and the fates of those in the tightest orbits around him. Characters age, mutate and transform themselves as Caden tries to play God but is done in at every turn by the simple fact that he's not cut out for the part.

Despite the general air of unpleasantness and anxiety, and the feeling that the film, like Caden, could explode from overloaded circuits at any moment, Kaufman's venturesome dramaturgy and compelling writing scene-by-scene are enough to keep one's curiosity piqued. Significantly crushed by illnesses, the drudgery of life and his failures with women, Caden doesn't seem like the genius he sees himself as, and the inspiration triggered by the sudden blessing of complete artistic freedom may also be only a figment of his imagination. Whatever the case , Hoffman embodies him completely, forcing the audience to share his every physical and emotional wound.

Along with Keener, who takes off early on, the other actresses shine as the women who both appreciate and tolerate Caden. Morton captivates as the adoring associate the director loves most, and Watson provides an ideal alter ego. Michelle Williams warmly shades the role of the theater company's leading actress, cast as Caden's wife in the theater piece; Hope Davis (who could play Hillary Clinton when anyone decides to do that film) sharply etches Caden's blunt shrink; Jennifer Jason Leigh disappears into a German accent in a very strange role ; and Dianne Wiest comes aboard as a late addition to the New York project.

Working with vet lenser Fred Elmes, Kaufman tends to keep his frames tight, provoking a claustrophobic feel that matches Caden's usual psychological state. Production values come to the fore as the “set” for the ongoing theater project takes shape with evocative verisimilitude, with production designer Mark Friedberg and visual effects supervisor Mark Russell and an extensive effects team earning good marks. The long arcs of Jon Brion's score go the extra mile to provide emotional continuity to the sometimes quickly changing scenes.

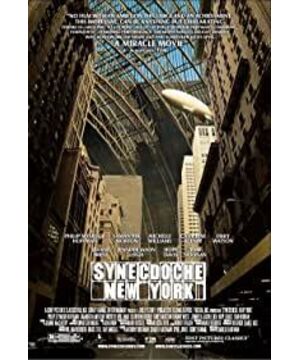

View more about Synecdoche, New York reviews