Perhaps it was destined to see this film on a rainy night in Shanghai, and it echoed the situation of the characters in the film. It is precisely because of the gradually cooling rainy night that he chose to stay in the hotel, and the protagonist Bobby described himself as being trapped in a diving bell, who suffered from atresia syndrome. It is not difficult to see that water, not only has the image of flow and life, but also brings some kind of suffocation and restraint to people. Therefore, the configuration of the film elements also unfolds from this, so we can see the seaside of Baker's hospital, the divers sinking into the seabed, the disintegrating glaciers, and the pool in the hospital. All these fields containing water, on the one hand, brought out Bobby's negative emotions, on the other hand, it continued his life. In such ups and downs, he was able to use his memory and imagination to get rid of the physical predicament.

To give us a sense of Bobby's physical restraint, director Julian Schnabel spends nearly forty minutes using a shot calling himself "me" (here Bobby). If you are familiar with film history, you will find that similar techniques have appeared as early as the silent film era. By the time of the talkie, however, after Robert Montgomery shot Lady in the Lake with a completely subjective shot, the practice all but disappeared. "A totally subjective film (in terms of sight, of course) can only be one in which the protagonist's vision is presented 'objectively' and the character is hidden behind what he sees. ("Cinematic Semiotics Questions", p. 108) Obviously, the director also understands that complete subjectivity is not desirable, so he uses these techniques relatively eclectically to match Bobby's situation, because he can't get more vision by moving his body. The camera only needs to use a small pan to mimic eye movements. Interestingly, when Bobby's right eye is stitched, the picture appears to be sharper, unlike the opening scene in the film: the right side is slightly blurred and sometimes has a small perspective distortion. It is probably this small difference that just corresponds to the malfunction of his right eye. "At a distance of twenty meters, binocular vision matches the perception of perspective captured by a monocular or an ordinary observer. To prove this, just close one eye and observe the outside world. Although the left eye is used Or when viewing with the right eye, the axes of the visual field are different from each other, and the field of view is significantly smaller, but the line of escape is exactly the same." ("The Semiotics of Film", p. This leads to another question. Although there are not many similarities and differences before and after observation with one eye, how should the camera be converted from two eyes to one eye when it is the existence of one eye and as "I"? In the film, a more direct method is used. After it is completely dark, it is cut to the sewed eye, and then it returns to the subjective point of view. Although this kind of treatment destroys the continuity of the technique, the director obviously has no intention to implement this idea, mainly using the too close distance to the subject to bring some kind of discomfort in perception, in response to the limited perception of the protagonist.

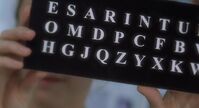

When the protagonist opens the door to his own consciousness, the film no longer unfolds the plot only through Bobby's point of view. In the scene where the two phone installers question Bobby in the ward, they also use a panning method, but there is only silence when the camera pans to Bobby's side. It's hard to tell the source of this sight, but this kind of onlooker will bring a kind of introspective ability to his narration. "The narration employs an introspective sense of tone and range to occupy a subjective world, as Proust's analysis does." (Cinematic Semiotics Questions, p. 175) Films like How Green Was My Valley's Brief Encounter contain no introspection, the narrator witnesses only objective reality. In later works influenced by Hiroshima, My Love, when it comes to themes of the past and memory, narration creates more possibilities. This narration does not provide an explanation for the image, nor does it use repetition to emphasize meaning. And when the complementary images and narration are perceived at different levels, the inner complexity emerges. When Bobby and the recorder were translating at the beach, his narration first appeared, followed by the sound of the recorder reading the letters, and then the two of them appeared on the camera at the same time. Because we can see the appearance of the protagonist, he does not say a word for physical reasons, and the narration acts as his inner monologue at this time. "I feel a little bit of self-pity, don't I?" Such a short narration is not only a question about the current situation, but also contains a sense of self-examination. The image and the narration say one thing, but express something different.

In addition to the recorder (Claude Mendibil) just mentioned, there are not many female characters around Bobby in the film, as well as the linguist (Henriette Durand) who helped him, the nutritionist (Marie Lopez), and the "Henriette Durand" who often came to see him. Wife” (Cine Desmoulins). There are also characters composed in his imagination and containing elements of memory, such as his former lover (Josephine) and the imaginary queen of Napoleon III. In fact, his lover (Elese) appears before all the other women, and in the blurry vision at the beginning of the film, we can see her furnishing Bobby's hospital room. Of course, this can be understood as the protagonist's imagination, the concretization of the idea of wanting to see his lover, but the photos and hanging paintings all over the room have become the traces that confirm the lover's arrival. It is probably understandable why, in front of his wife, he can still express the feeling that he is waiting for every day. From this point of view, the director seems to have a certain homogeneity in the choice of the main female characters, hoping to make up for the absence of his lover (Elese) regret. At the same time, it also brings some help to the memory and imagination conveyed by the images. It is precisely because of the similarity that we can touch emotions and regenerate corresponding memories, which also produces surreal fragments. Like in the middle of the night, listening to the mechanical noise of the TV, Bobby senses the restraints of the underwater diving bell, and by looking at the memories on the wall, the glacier of his mind begins to collapse.

Compared with water flow that is not fixed in form, glaciers have certain shapes and layers, and must be formed after a long period of environmental action. In contrast to the plight of locked-in syndrome, this collapsing glacier is not necessarily all negative and negative images. Because of this active disintegration, it brought out the image of the butterfly that was superimposed in the hospital sky, and the butterfly of his thoughts finally broke out of the cocoon. . At the end of the film, the glacier reappears in the form of reset, but this is not a reversed image of the previous glacier disintegration, but another piece of glacier footage. Because of the similarities and differences between the two glaciers, we can realize that what Bobby remodeled is no longer the original thoughts and concepts. Even if his life is about to run out, he wrote the book "The Diving Bell and the Butterfly" with his eyes. ” remains a continuation of other forms of his own, just as this shattered and reconstructed glacier…

View more about The Diving Bell and the Butterfly reviews