Disclaimer: This article is a personal work, and no one may intercept, reprint, plagiarize, or use it for commercial purposes without authorization.

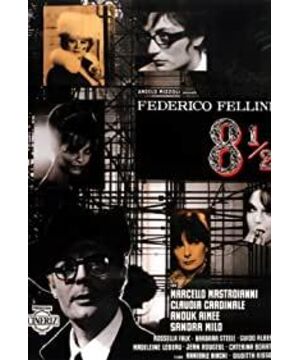

Federico Fellini's paradigm-shifting movie 8 ½ (1963) presents a liner-time story that successful director Guido Anselmi is struggling with the double pressure of conceiving a well-expected film and the turmoil of his emotional relations, while nested dreams and hallucinations restlessly penetrating and blending in his real life. In reality, Fellini himself was exhausted by world's high expectation on him after his triumphant La Dolce Vita(1960) and stagnated in a composition crisis. Exactly resonating with his experience, this movie is Fellini's “eighth and a half” movie (six films plus one cooperated film plus two short parts), and hence the name. This fascinating homogeneity between Fellini's reality and Fictional Guido, as well as the practical world of Guido and his fantasies, provides much space for discussing the conflicts and coordination of fictions and reality, as Costello (1981) did. Despite the movie's richness in content, I will focus on layers of functions of Claudia in Guido and Fellini's fantasy-dream-reality complex, as well as the three potential “solutions” at the end of the movie.

Claudia is first and foremost Guido's idealized women and then a character in his film (Costello, 1981). Claudia enters Guido's imagination in a white dress (7:49), symbolizing purity and order. She delightfully runs to Guido, smiles in a pleasant and adoring way, and offers him a glass of mineral water. Back to reality, on the other hand, it was a busy woman, who clearly is bored by her tiresome work, fills Guido's glass with mineral water. After Guido was stressed out by the present of his mistress Carla, the French actress who bothering Guido about her character, the phone call from his wife Luisa, and the expecting staffs, Claudia once again accompanies him, obediently making bed and “becoming” the daughter of town museum curator ( 52:53). This fantasized version of Claudia satisfies Guido's masculine desire: while Carla,Luisa and other people are demanding Guido, Claudia provides comforts and doesn't require commitments. However attractive and sexually appealing she is, the ideal Claudia remains pure and unsullied, “a symbol of purity, of sincerity,” and a visioningobject a . Similarly, Guido's harem fantasy, that relates more with sense of security rather than sexual desires.

Then Claudia is the actual actress for Guido's film, as well as Fellini's actress in reality (Costello, 1981). The actress who played the role of Claudia in 8 ½also named Claudia, and thus extending the complementary fantasy of Guido to Fellini and to audiences. At first, Claudia frees Guido from the stressful screening and from his intractable producer, especially when his wife decides to leave him. Nevertheless, the disenchantment has started. In contrast with the white clean-cut dress Claudia, the actress Claudia appears in a gorgeous black dress with feather decorations (1:56:15). As McGowan (2011) points out, Guido has been hesitating among all the possible options—Carla and Luisa, castings, themes and plots of his movie—because he cannot embrace that “enjoyment must necessarily be partial.” The inaccessibility of object ademonstrates the impossibility of full enjoyment, yet Guido couldn't let go of the image of total enjoyment and thus wanders across his fantasies and reality. “There is no doubt that she is my only hope,” Guido said to Claudia (1:59 :09), while understanding that his image of fantasy on an elegant yet youthful girl-woman abdicates to the reality of partial enjoyment.

After Guido terminates the started new movie, the people to whom he emotionally attached to are now dressed in white, smiling in a state of relieving, pleasant and order, and the ideal Claudia retreats in barefoot and lively mood (2:09:27) . The fantasy and the last hope of full enjoyment leaves Guido, and suddenly all other people in his real life descend accompanied by the circus band (2:15:52). Guido comes to the center of the pit, conducts the crowd and thus his life, and finally joins them. While the retreat of the ideal Claudia represents Guido's disenchantment on the pursuit of object a, the ending contains three solutions which distinguished by the acceptance of this disenchantment. While Costello (1981) states the circus scenes as movie's ending “in reality,” McGowan (2011) suggests that Guido remained within his imaginary. I, nevertheless, consider the “fantasy (in cinematography)” suicide, the termination of movie projects, and the circus fest are parallel solutions to Guido's crisis. When Guido cannot face the disenchantment on preserving the image of full enjoyment, suicide seems the plausible way-out; when Guido is capable of embracing the failure of pursuit of object a , he can easily let go of the holding movie project. The state of Dionysus, the madness and the revelry, is the irrational solution out of the paradigm. On one hand, our recognition of object aoriginates from the miscomprehension of the Other's expectation. An infant finds joy and satisfaction on his or her mother's face when she is looking at the infant in mirror, the ideal ego which he or she thought more “whole” or desirable to their mothers. On the other hand, our perpetuating pursuing of object a, in many occasions, constitutes the expectation and even object a of the Other. For example, when a child endeavors to meet the expectation of his or her parents, his or her parents also consider the A “better” version of the child as object a . This cyclical relation demonstrates a dilemma that while subjects try to comply with the Other's desires, the Other doesn't know what it lacks from the subjects as well.

Work Cited:

Costello, Donald P. "Layers of Reality: "8½" as Spiritual Autobiography.". Notre Dame English Journal , Vol. 13, No.2, Spring 1981, pp.1-12. The University of Notre Dame .

View more about 8½ reviews