The story begins with the encounter between a scholar and a woman and the telling of the story. The heroine has a kind of indifference and fragility, emotional and repressed beauty. I would like to say that the heroine has no passion. The heroine does not have passion and affection in love, but she is honest and pursues physical desires. Is the heroine honest about her desires, or is she escaping from feelings, or is it two sides of the same coin, because people can only devote their attention, control, and power to one thing? The first part does not give more clues to draw a proof. But there are clues indicating that the heroine does transfer her emotions to sex, and sex is used as an expression and catharsis. This is the second half of the matter related to the father. So in the first half, the heroine in front really just looks like a naive and cruel beauty. Compared with her friends, the heroine is the real indifferent, brave and powerful image. People who seem to be outspoken and arrogant finally show the characteristics of normal people, while the female protagonist who is calm and indifferent and not outgoing is more ordinary and deviated from the normal track. The former is a teenage rebellion, and the latter is an exploration of life. Seems like an exploration of life, not life. The encounters with scholars did not show more content in the first part, but the academic discussions of scholars are very interesting. What I've been thinking about lately is when an academic discussion is meaningful, that is, when it does reveal some truth. I think the purpose of scholarship is to reveal truths, not answers. Reality may not have the answer. Reality is a theoretical, logical, emotional, practical possibility. Some things do not happen in theory, but in reality, this is true, and some things do not exist in reality but theoretically possible, too. Some things hold up logically, and some things exist emotionally. Reality covers it all. But in this sense, whether the work reveals the truth still needs the understanding and experience of the audience. Perhaps the criterion of good or bad is how close it is to the general human experience. But of course, a standard is just a standard.

There are places where academic or artistic discussions make me feel relevant, like the author speaking to the audience, or talking to himself. Because there is no listening object at this time, there is no object's situation and needs, and there is no relationship between the two, so you can dig deep and mysterious content as much as possible. While the heroine talks about her own experiences, while the scholars talk about the knowledge about nature, mathematics, and art, this constitutes a too obvious polyphony. Similes and symbols are tedious from the point of view of real-life dialogue or the characters in the play. Unintentional, coincidental symbols are better. But from the point of view of showing and telling, polyphony may also work.

In the face of vivid experience, is scholar's knowledge an abstract sublimation or a boring dead thing? I do not know either.

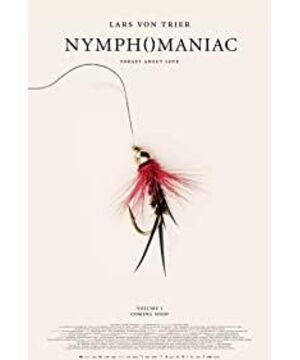

View more about Nymphomaniac: Vol. I reviews