translate:

Sometimes you just have a vague idea in your head, and it takes years to figure out where the story should start. Often, you have to wait for the half-formed concept to merge with other ideas before inspiration strikes.

That's how "Zima Blue" was created, the second Carrie Clay story in this book. I've always wanted to write stories about robots that have been passed down through the generations as heirlooms over the centuries, getting smarter and more refined over time, I know Isaac A Isaac Asimov has already 'used' the concept in his novel "The Bicentennial Man", but what's really pleasing about science fiction is that it involves much more than New concepts are more about finding new angles to understand existing concepts. What you need to do is to find your own angle of understanding, and use new narrative methods to clarify new truths. Needless to say, this part is the most difficult.

'Zima Blue' was put on hold for many years until I found the other half - a whole new angle of elaboration. During this period, I tried to clear my mind by swimming, and inadvertently figured out the key.

The swimming pool is really a nice place.

Since 'Zima Blue' is about the fallibility of memory, it only makes sense to document my own uncertainty about an anecdote in the text. I mentioned the story of a man who was desperately searching for a certain blue he had seen in his childhood and found it in a beetle at the Natural History Museum. This happened to neuroscientist Oliver Sacks: At least I remember him talking about something similar on a TV show, sorry if I remember the details...but I just want to reiterate my sympathy for Sacks The love of the work, and the amazement and awe I experienced when I read his biography. If science fiction doesn't exist in this universe, then Sachs's work fills that void very effectively.

Note:

1. "Zima Blue" from Alastair Reynolds' collection of novels "Zima Blue and other stories"

2. The Double Hundred is a novel by American author Isaac Asimov, which won the 1976 Hugo Award and Nebula Award for Best Science Fiction.

3. Oliver Sacks, a famous neuroscientist in London, UK, is good at writing clinical cases of cranial nerve patients into profound and touching stories in the form of non-fiction literature and full of humanistic care. Both enjoy a high reputation and have been named "Poet Laureate of Medicine" by the "New York Times".

original:

Sometimes you have half an idea for a story that you hold in your head for years before you know what to do with it. Typically, you have to wait for the moment when that half-formed idea intersects with another one and the mental fireworks go off.

That's how it was with 'Zima Blue', the second Carrie Clay story that appears in this book. I'd long wanted to write a story about a robot that had become a kind of family heirloom, passed from owner to owner across many generations and centuries, with the robot becoming cleverer and more sophisticated as time goes by. I was well aware that the idea had been 'done' by Isaac Asimov in his long story 'The Bicentennial Man'. But one of the truly delightful things about science fiction is that it is far less about new ideas than it is about finding new ways to think about old ones. All you have to do is find a new spin, a new way of telling, a new truth to illuminate. Which, needless to say, is the difficult part. 'Zima Blue' sat on the back burner for years until I got the other half of the story,the new angle of attack. And I got it while taking a swim to clear my mind of the problems I was having coming up with story ideas.

Good things, swimming pools.

Since 'Zima Blue' is about the fallibility of memory, it's only fitting that I should record my own uncertainty about an anecdote in the story. Mention is made of a man who searched despairingly for a particular shade of the colour blue glimpsed in childhood, and who later finds it in the colour of a beetle in a museum of natural history. I think something like this happened to the neurologist Oliver Sacks: at least, I remember him talking about something very like it in a television programme. If I' ve misremembered the details, I apologise . . . but I can only restate my enthusiasm for Sacks' writings, and the many moments of jaw-dropping awe I've experienced in reading his . If science fiction did not exist in this universe, the writings of Sacks would fill the gap pretty effectively.

—Alastair Reynolds

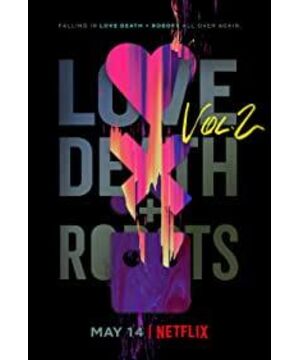

View more about Love, Death & Robots reviews