In "Manhattan," Issac, played by Woody Allen, has passed his old age, divorced twice, and fell in love with Tracy, a seventeen-year-old high school student. In the first scene, Issac teases himself, saying he's old enough to be Tracy's dad. The huge age difference makes it hard to believe that there will be true love between Issac and Tracy. On the side of Issac, this is more of a mediocre or even a failed life, a brief encounter, a well-known fling; on the side of Tracy, it is more like a Platonic spiritual dependence, a kind of infatuation.

Tracy has been trying to find out if Issac is really serious about her despite her cynical appearance; Issac is deeply involved in the process of accompanying Mary. Tracy's unrequited love and her unbalanced relationship with Issac doesn't materially change until the end of the film. After Issac was ruthlessly abandoned by his girlfriend Mary and indifferently cut off by his friend Yale, he began to think about what makes his life worth living. Lying on the sofa, he listed a long list of people and things to the tape recorder, from the TV star Groucho Marx, to the music giant Louis Armstrong, to the painter Cezanne, until he said "Tracy's face", and he ended with satisfaction.

Discovering the weight of Tracy in his own life is a very core part of Issac's self-awareness and self-awareness. When chips are down, Issac's recollection of looking back is more readily accepted as an expression of deep love. If Issac had previously treated Tracy with a "mocking" suspicion, he seemed very sincere at this point. This change of heart makes Issac's feelings for Tracy gradually deepen and sublime, and in the last scene he runs all the way to Tracy's apartment to keep the latter's behavior moving and lovely.

This delicate feeling of being moved by love is actually very fragile, especially when we learn of the suspicion of child molestation between Woody Allen and his adopted daughter. Some people say that these scandals have made people have to re-examine this year-old relationship that was admired in the film, and then feel that their aesthetic feelings have been ruthlessly stained. We can't empathize with the "self-justification" and "self-glorification" carefully created by a person with moral taint in reality, and it is even more difficult to identify with the value tendencies revealed in it, either overt or covert. We can't be indifferent and sit idly by; we can't condemn a person and like his creation.

This category of people has an underlying tendency towards moral supremacy. For them, the reason a director's real-life moral indebtedness offsets the artistic value of his creations is because they believe that moral value rightfully trumps artistic value. Therefore, our attitudes and perceptions of a person's artistic creation should be influenced and synthesized by our moral evaluation of him. Of course, the controversy brought about by this tendency is obvious. Moral supremacist judgments confuse moral value and artistic value, two independent values that we intuitively believe that well water does not violate river water. Therefore, to examine a person's artistic creation from a moral point of view is itself an arrogance of moral value, and a disregard and betrayal of artistic value. In the eyes of art autonomists, this pan-moralizing tendency leads to horrific censorship and self-castration, and it is a harm to the independence of art and the creativity of artists.

We, caught up in this controversy, are pulled by both sides. On the one hand, we sincerely want to defend the independence of art, but at the same time we are worried that artistic autonomy will become a pass for shameless behavior and a card from death; on the other hand, although we are wary of the side effects of pan-moralization, we still take moral values seriously and hold the utmost respect. This may be an excellent illustration of what Murdoch calls "complex reality": different values are not parallel or even mutually exclusive, they are superimposed and influenced by each other in ways that we do not yet fully understand, and the complexity and confusion of their relationships deserve our attention. and respect. In this sense, the advocates of moral supremacy and artistic autonomy have mistaken the "partial truth" for the "full truth" of our value field, which is indifference to our fragmented value life.

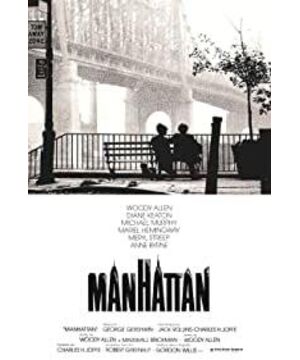

View more about Manhattan reviews