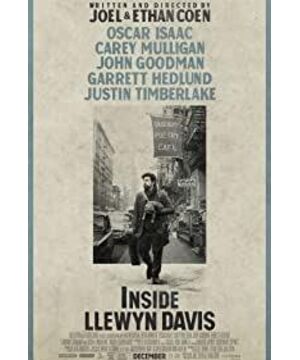

"Drunk Town Ballad" lives up to its name, loose, with a bit of casual hilarity and road-movie oddities that come and go. people and all-encompassing pop culture.

The film was inspired in part by Dave Van Ronk, the ex-Bob Dylan-era folk singer who, like Liewyn Davis, was scruffy and distressed, and never really became a star.

So, "The Ballad of Drunken Township" isn't some old tale of a talented artist destitute and waiting to be discovered, as we've been expecting. His old fox manager treats him like a beggar, it's okay; "You're not the one standing in the foreground", the big boss of Corner Gate Productions told him, it's okay; even we will ignore that he's not so innocent, just like Jean Said he was "the stupid brother of King Midas who turned gold into gold", and everything he touched turned into shit. But we don't care. Because we were secretly looking forward to the eventual turnaround, Llewyn Davis was admired and made famous.

Until the end of the film, we see a young Bob Dylan—yes, that was the voice that started an era—Llewyn Davis, whose traditional melancholy lyrical tunes are beautiful but not great enough.

In fact, we should have expected Llewyn Davis to be just the latest exhibit in the Coen Brothers' underdog gallery. They are bitter and self-regarding, but they don't even realize that their lives are actually being dominated by others (or the whole world) and their own stupidity, and they have become the playthings of the ruthless God of Destiny.

But maybe it's because Oscar Isaac is so charming; maybe it's because he's a cynical bastard who sings to capture the good and the pain in life; or even because the Coen brothers are so emotional about their characters this time around (Oh man, they rarely love their characters).

So, we both laugh (with a little sympathy) at Llewyn Davis and join him in laughing at the idiots he laughs at.

It's a little weird that "The Ballad of Drunken Country" may be the Coen Brothers' warmest film to date. The cinematography of old partner Bruno Delbonnel gives the film the softness of an old record jacket. Gray tones in the dark, bright white halos; half deliberately worn, the other half polished. It seems to carry excessive nostalgia, it feels strangely unreal, and it imbues an almost tragic story with a lyrical version of dreaminess.

And at the end, the film loops back to the beginning of the story, with Llewyn Davis lying on a street corner with a bruised face - our Ulysses is not going anywhere.

Highlight: Llewyn Davis pouted and ran across the subway car trying to catch the big yellow cat. ps. That cat (or two cats) contributed the best cat performance since The Long Goodbye.

Originally featured on Universal Screen

View more about Inside Llewyn Davis reviews