1:46:34∽1:59:00 Workers riot, destroy machines, and cause disasters in dungeons

As the grandest scene in the entire film, the workers' uprising represents a resistance to oppression. The director used a large number of group performances and spectacular pictures to express this long-standing " resistance ", but we can find from this scene that such "resistance" was not successful.

The fake Maria used an exaggerated expression of "winking" to incite the workers to "die for the machine." The director uses a panoramic lens to show the crumbling elevator full of people, the violently demolished railing, and the workers climbing up to the railing with a hammer from multiple angles of head-up, down and up. There is a huge contrast with the workers at the beginning of the film, walking with their heads down and walking to and from get off work like dead bodies.

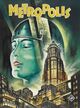

In an industrial society, workers are just a screw in the production line. They are alienated by machines and lose their self-awareness. At this time, the fake Maria makes them suddenly re-recognize their needs and desires, which triggers a series of extreme and distorted behaviors. This is also one of the connotations of German Expressionism: exposing the sins of the metropolis and venting the inner madness.

It's a feast of violence - in contrast to the peaceful scene before Maria with the children, with an almost barbaric narration of the transformative riots that take place in a city that represents "civilization", both as a story of oppression And the inner anger of exploited workers is also an expression of condemnation of reckless violence.

The destruction of the core machine by the workers caused the water to flood the dungeon, and the children wanted to rush up to the high platform to avoid the flood water rushing from all directions. The children are pure, kind and innocent. They don't seem to feel the pain of the adult world, but they are the children of low-level workers who live underground and are destined to be accompanied by darkness. More and more children are running from all directions, but the small high platform cannot save them - the reason is that children are symbols of holiness, and violence must not be used to save them from the dirty underground.

The close-up shows the horror and helplessness on the faces of the children, who gather in front of the stage and raise their hands in anticipation of true Maria's redemption, a sharp contrast to the frenzied raising of their hands in response to the previous episode, when the workers were Dancing hand in hand, ignoring the disasters of the outside world, it is extremely sarcastic. The director may want to use a "karma" perspective to explain: irrational violent actions will eventually cause harm to their own children and even innocent people.

In this scene, we can certainly read metaphors about religion , from the female teacher Maria in the flood to the Virgin Mary in the Bible. In addition, we can also see: under the cloak of religion, is the Class antagonism and conflict.

This has a lot to do with the background of the time. America ushered in the "Coolidge Boom" in the 1920s, and at the same time it brought about a boom in capitalism as a whole, including the German market. Just when everyone thought "permanent prosperity" was on the horizon, a devastating financial crisis broke out and capitalism plunged into an unprecedented Great Depression.

This play is a reference to the era. German society is seriously polarized - the upper class enjoys luxury, the lower class is hungry, and the contradiction between capitalist socialized production and private ownership of the means of production is extremely sharp. In this scene, the director implicitly expressed his understanding of the social status quo: "The regulator of the hand and the brain must be the heart", the workers' anger cannot fundamentally solve the problem, their children, or the descendants of the working class , will still face an existential crisis.

The Flood has a deeper meaning in the Bible, "The LORD saw the wickedness of those who were on the earth," and then he sent the Flood. In this scene, floods have a similar metaphor, violence begets floods, and floods lead to greater violence. It was the gentle and kind "Virgin Mary" who rescued the child from the flood, through which the director expressed his political views: in the face of class divisions, he advocates peaceful ways to ease class conflicts, and opposes complete violence for rights.

This group of workers is a rabble that has lost the ability to think independently and is easily incited, so the riots they have launched are of no benefit to themselves and only added disaster to the world. But it doesn't mean that all the proletariat should be submissive and look forward to a phantom "regulator" to achieve liberation. In history, the Communist Manifesto, "the proletarians of the world unite", the practice of the October Revolution in the Soviet Union, and "power comes from the barrel of a gun" have long proven that, under the guidance of a scientific program, a group of proletarians with a clear understanding of social reality can Successfully used violence to overthrow bourgeois rule and fight for freedom. Perhaps the director's hope has not been realized in the torrent of the times, but his thoughts are at least from the humanistic perspective of "civilization defeats violence", and it is also worthy of learning from the current era.

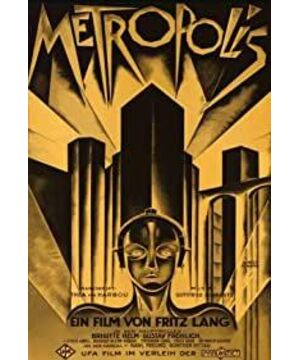

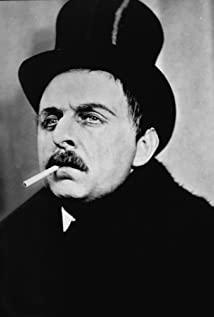

View more about Metropolis reviews