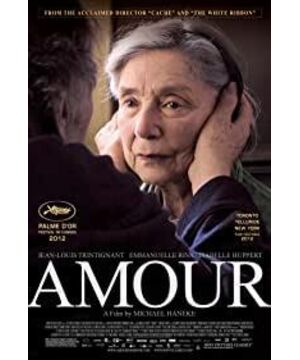

"Amour" follows the usual one-line narrative in Haneke's works, with only a flashback in the opening that disrupts the time: the firefighter smashed open the door of an apartment and saw the dead Anne lying flat on the bed with her pillow covered. Flowers. The rest of the film is completely flat and straightforward. Haneke uses his cold camera to start a journey of death:

the old couple Anne and George, who are over eighty years old, are both retired music teachers in Paris, and so is their daughter Ava. A musician who lives abroad with his family. The couple went to the concert together, took care of each other's lives, and lived quietly and with dignity. One day, Annie suffered a sudden stroke and underwent surgery at George's insistence, which caused her to be paralyzed on the right side of her body and had to rely on a wheelchair. George drags her aging body to take care of his wife. Anne is more sensitive inside. The visits of students, neighbors and even her daughter will make her irritable and painful. Once George went home from a funeral and found Anne collapsed by the window, Anne tried to commit suicide by jumping out of the window. After Anne suffered a second stroke, because George promised Anne would never send her to the hospital again, he had to ask a part-time nurse to take care of her at home. Her condition was deteriorating and the situation was horrible. George watched in pain, watching her gradually lose her language function, and she could not even express her pain in a sentence, calling "mother" and "pain" all night. Finally, in order to save his wife from illness and self-esteem, George smothered his wife to death with a pillow.

Even Haneke, who has moderated, still has to face many criticisms. What should we do when our loved ones suffer? Haneke offers a possibility in the movie, which is naturally not the best way. Everyone has the right to live. Even if she desperately wanted to jump out of the window to commit suicide, even if she unconsciously yelled "pain" all night, even if she had to face her shameful incontinence, she still lived. Right to go down. But is this love? For whom is it for me to continue the meaningless life? However, covering her to death with a pillow is probably not love either. Putting it in life, this is an unsolvable problem. Fortunately, this is just a movie. There are thousands of ways, thousands of expressions, and annotations of love, only right or wrong. Even killing, in the name of love, is a gentle killing; no matter what decision is made, it feels inappropriate after all. Can only take the first step cruelly. The consequences that follow are pain and relief, and they can only be accepted in full according to the weight of love, whether light or heavy. After George sealed the bedroom door with tape, the pigeon flew into the living room again. George finally grabbed it with a blanket, and he held the pigeon tightly, and gently stroked the pigeon wrapped in the blanket, just as he gently stroked Annie's face before. I think this is a relief for George. He left a letter. It seems that he can still hear Anne washing dishes in the kitchen, and see her red nose, and hear her abusively remind him to wear shoes and coat. I can still hear her say "merci" in a nice tone, and he is going out with her. A far door at a time. I believe that the letter he left is the last tenderness. The so-called open ending is nothing but the concise film language used by Haneke.

Haneke's description of aging and death is cold and unconcealed. After the right half of her body was paralyzed, Annie was vague and couldn't speak a complete sentence; her body was stiff every time she got into the wheelchair; after incontinence, she was embarrassed and pissed that it was difficult for her wheelchair to squeeze into the narrow door when she wanted to enter the living room. Haneke used long shots to take pictures of Anne's embarrassment and embarrassment, and George's old age should not be ignored. He was always struggling to hold Annie; his bad temper broke out suddenly when Annie refused to drink water; he had to pause for a long time after he stood up to stretch his legs. It is also worth mentioning that George attended the funeral-an absurd farce dictated by George. Everyone was laughing when they saw the urn placed on the electric car slowly sliding into the coffin. These details make the problem more complicated from all dimensions. The physical weakness and shame caused by aging, the dispersal and indifference of the extended family, and the lack of human affection...all make it impossible for the problem to be judged by simple and crude moral standards. Like the usual Haneke movies, the scheduling, movement and environment of the shots are all minimalist. His lens is fixed there, not even moving, to capture the entire scene. The telephoto and the long-term fixed lens make the picture of the movie seem to be still, and there is nowhere to escape the pain, and the beautiful love of the two old people is the same.

I remember that a long time ago, there was a doubt, since there are photos, why are there still realistic paintings? Similarly, since there are real life and documentaries, why are there still films in the style of realism images? Haneke has almost taken away all his subjective feelings, making the audience deeply feel the feeling of "I am a bystander". He is powerless and can only accept it. Haneke said after winning the award, "My own impression of this theme (old age) is that in most cases it is politicized. In fact, there are many movies about the fate of old people. I did not adopt it. A similar technique, because I think it is a very main proposition in itself." In "Amour", he tells death in a calm and cruel manner, and depicts love in a meticulous and warm manner. This kind of amour is not intense, and even the desire to survive. None, only the companionship at the time of life and death. If Hanek is a monster, it must be the gentlest monster.

View more about Amour reviews