Since I started filming, I have watched more and more movies, and the level of watching movies has become higher and higher, but I like less and less movies. I don't know why, while my appreciation level has become higher, I am becoming more and more harsh on movies, and there are less and less things that move me. Now my favorite and most familiar movies are still those who liked it before they studied movies, most of which are Wong Kar-wai and Iwai Shunji. The taste of adolescence is fixed at that stage. After that, no matter how you improve your level rationally, emotionally, your original intention is still insurmountable. It's like other film masters are works of art displayed in museums for study, but the original intention is to paste the replica posters on the walls of their rooms. Although they may have never touched the original version, what they have is just an illusion, a mass production. A cheap product, but because it was hung on the wall of my home, I accompanied myself when I was young, and it became part of my self-awareness. This perceptual cognition cannot be surpassed by any means. However, after studying film, I was able to appreciate more difficult and incomprehensible films. At the same time, the situation of film mobilizing rational thinking gradually caught up with the experience of using pure sensibility to sink in easily, and the degree of being moved always restrained a little. While considering the sound and picture, the plot, the characters, and the philosophy, the innocent audience gradually exited in my body, and only occasionally appeared for a while, applauding alone in an empty movie theater. Most of the time, she is forgotten.

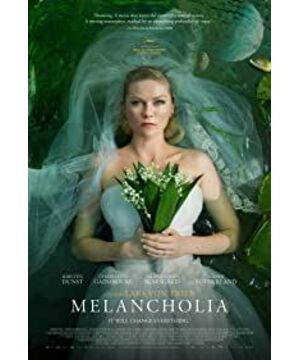

Even so, there are some movies that go a little deeper. Whether it is the subject matter, the way of expression, or a detail, I can mobilize my emotions to respond to it in addition to rationally judging its pros and cons. Melancholia is one of them. This is the kind of film that after I watch it, I feel like I have completed a self-education in the field of film, and I am glad I have seen it.

Because of my emotions, I once looked for movies related to depression, but most of them were unsatisfactory. In Japan, there are "Husband Has Depression" and "Only Love Can Make Me Survive", but no matter which one is a commercial film with a touch of water. In my very limited viewing experience, I think these two films are the most accurate in portraying the state: "Melancholia" and "Manchester by the Sea." Among them, "Melancholia" is more attractive to me. The director of Melancholia, Lars von Trier, was a Danish film master and one of the founders of the Dogme 95 movement. The first film I saw of him was the shocking Woman Addict, which I still find amazing. Another promoter, by the way, is Thomas Vinterberg, who is no stranger to the mainstream film market, director of the Danish film "The Hunt" and most recently "Alcohol Project" Nominated for last year's Cannes. His Dogme 95 classic "Family Dinner" managed to make me sleep soundly when it was screened in class. In fact, every Dogme 95 I've watched has put me to sleep.

Dogme 95 is a film movement launched by these two young Danish directors in 1995, with the aim of "purifying" films to a relatively "absolute" "truth". The dogma includes: the film must be shot on location, all props must exist naturally on the shooting site and cannot be brought from other places; the recording must be synchronized in the field, and there must be no post-production sound and music; hand-held photography; must be in color Movies; no artificial lighting or special filters on the lens (if the natural light is too dark, the scene can’t be filmed); plots prohibit overly entertaining scenes such as murders and weapon fights; movies can’t strip time and space Kailai (the movie takes place here and now), and the director cannot be named.

These overly harsh doctrines made it difficult to implement, and the two directors themselves were unable to fully comply. After a series of experiments, the movement went bankrupt 10 years later, but left behind a long list of Dogme 95 classics.

The biggest features of the Dogme 95 film are the rough hand-held camera movement, impromptu zoom and focus, completely natural lighting, and very deep, tricky, and even brutal human characterization. This is a movement that sacrifices the sense of picture in order to fully immerse the performance in reality. To a certain extent, it seems to restore the original intention of the filmmakers. But somehow, I don't like Dogme 95, and I slept in a lot of Dogme 95 classics in class. Once I woke up in the middle of a sleep and found that all the characters on the screen were having sex. All of the sex scenes also take place completely in front of the camera because of the real performances that Dogme 95's dogma demands. Such absolute truth has created an absolute false illusion. The actor is the character himself for a moment, and the behavior of the two cannot be separated. The truth of sex extends to the body of the real actor, but it is because of a false premise. Looking at such a scene, it is like watching a collective hypnosis. So I was hypnotized to sleep again.

The two directors are no longer bound by their own dogma, but they still maintain a part of Dogme 95's character. Both of them still have a penchant for handheld photography and slightly fragmented editing.

Handheld photography is not why I like The Melancholia. When watching a movie, I hope the picture is steady, far, slow, and the editing is not so fragmented. But I don't need to like everything about a movie anymore to like it. In fact, growing up, I've been unable to find anything I totally like. Everything is like a bag of Bibi Da flavored beans, with a good taste and a disgusting taste. All we can choose is to endure it until we taste it, or to give it up. This is one of the truths of this world.

It's hard not to think of Ophelia who drowned in the film's poster. In fact, Ophelia's oil painting did appear in the film. In a suffocating wedding banquet, when the heroine was frustrated and took down all the modern abstract art albums in the study and replaced them with classical art albums, there was this painting of Ophelia. This scene seems to be a revolt against the superficial modern decorative arts, and it can also be understood as the heroine's contempt for her profession: the advertising artist industry. She chose to return to one of the most iconic images of melancholy in the classical literature.

The title of the film does not use the more modern term "depression" but the more classical and poetic term "melancholia", perhaps also to distance itself from the medical condition, so as to be able to go deeper. Understand the nature of depression.

The first part of the film spends an hour depicting an obnoxious grand wedding reception and its debacle. Kristen Dunst's heroine, Justin, starts out looking like a spoiled bride, heavily makeup, happy and stupid. In the fast-moving handheld photography, the eyes can't stop somewhere, but can only glance at the wedding banquet of the century, making people restless and unable to rest. Disturbing factors gradually emerged one by one: the heroine's romantic father, world-weary mother, brother-in-law who is extremely wealthy and thinks money can buy everything, understands her but is also tired of her sister, can't get out of her heart Gone husband, and an egotistical nasty boss. At this extravagant wedding banquet hosted by her sister and brother-in-law for herself, despite her best efforts to force a smile, her relationships with those around her were disintegrating one by one. She couldn't get out of her blues, so she couldn't fit into what her family thought was normal. Many people around her think that money can solve her troubles, but her negative attitude annoys them all. First was her brother-in-law, who suggested that the wedding banquet he spent astronomical amounts on had only one condition, and that was to make her happy. Then there was her boss, who was still urging her to work on the day of her wedding banquet, and forced her to fire a newcomer on the spot. Finally, her husband, to please her with a superior life in the future. But she couldn't be happy, and she couldn't meet her brother-in-law's request. She fired her boss. She pushed her husband away, who couldn't understand her, and their relationship ended on their wedding day. She begged her father to stay, but his father was more willing to follow his new love. The utterly misanthropic mother understood her but could no longer help. The older sister was at ease, unable to understand why she was always dissatisfied with the superior life. She is a melancholy person, and all her melancholy behaviors and negative attitudes are seen as a rebellion against her family's way of life, with whom she cannot create the wonderful illusion of high society luxury, so she has nowhere to go.

The contrast between richness and emptiness is magnified to the extreme. In this decent world, grief seems to be the original sin.

My sister asked the bride who was snoozing in her nephew's room at her wedding, what was the matter with you, and the sister said: I was walking through the grey woolen threads, and they entangled my hands and feet. I dragged them when I walked. very heavy.

The melancholy image of Justin struck me not only because she portrayed such a melancholic who was not understood by the world and accepted by all close people, but because her melancholy came from a sense of emptiness. sensitive. This emptiness was not noticed by everyone else, and only affected her alone. She sensed the emptiness in intimacy, the incomprehensible emptiness between people, and fell into it, deeply, extremely tired of any superficial social interaction, and began to have a gap with the world . Just as her horse won't cross a small bridge no matter how hard it beats, she can't force herself to ignore what she's already feeling, and she slips into a crevice on the edge of the normal world. In the first part of the film, the "full" visual experience woven by luxurious scenes and trivial shots also pushed us to "empty".

The second part of the film depicts sister Claire's melancholy.

In this part, the audience is able to get more breathing room. Both the photography and editing are a little calmer to match the slow pace of the plot.

Sister Justin's depression is already very serious. She couldn't move on her own, and she didn't have any motivation to drive her body to walk or even lift her legs. Older sister Claire worries about a possible end of the world while caring for her deeply depressed younger sister. An asteroid called "melancholia" is flying toward Earth. It might not hit, or it might hit. Claire, and the world, fell into depression and anxiety about "depression".

Claire sinks into depression, dreading the catastrophe that could take her entire life away. She started showing up outside in her pyjamas more and more often, and her life slipped into fear. But she found that her sister Justin seemed to be showing signs of improvement, even more accepting and embracing the exoplanet whenever she fell into a deeper fear of it.

For a man who does not love the world, the end of the world is a relief.

From another point of view, the feeling brought by the asteroid "depression" is nothing new to my sister. When her pain is externalized to others, it has a therapeutic effect on her. She is no longer a marginal person in a world, but has become a prophet. In this world on the verge of destruction, the world's fear and despair are not the same as she has not experienced before, the world has slowly become her known and familiar.

I understand people who don't like this movie. In a sense, it is a very "ugly" movie. After all, the entry point is very partial, and the empathy point is very difficult to find. Its ending is also hopeless, and the film and television language is not close to the audience. But is there a more romantic way to cure melancholia with the death of the whole world?

View more about Melancholia reviews