-

Narrator: Something had happened. A thing which, years ago, had been the eagerest hope of many, many good citizens of the town, and now it had come at last; George Amberson Minafer had got his comeuppance. He got it three times filled, and running over. But those who had so longed for it were not there to see it, and they never knew it. Those who were still living had forgotten all about it and all about him.

-

Lucy: What are you studying at school?

George: College.

Lucy: College.

George: Oh, lots of useless guff.

Lucy: Why don't you study some useful guff?

George: What do you mean, useful?

Lucy: Something you'd use later in your business or profession.

George: I don't intend to go into any business or profession.

Lucy: No?

George: No.

Lucy: Why not?

George: Well, just look at them. That's a fine career for a man, isn't it? Lawyers, bankers, politicians. What do they ever get out of life, I'd like to know. What do they know about real things? What do they ever get?

Lucy: What do you want to be?

George: [fatuously] A yachtsman!

[Lucy reacts with astonishment]

-

[first lines]

Narrator: The magnificence of the Ambersons began in 1873. Their splendor lasted throughout all the years that saw their midland town spread and darken into a city. In that town, in those days, all the women who wore silk or velvet knew all the other women who wore silk or velvet, and everybody knew everybody else's family horse and carriage. The only public conveyance was the streetcar. A lady could whistle to it from an upstairs window, and the car would halt at once and wait for her, while she shut the window, put on her hat and coat, went downstairs, found an umbrella, told the girl what to have for dinner, and came forth from the house. Too slow for us nowadays, because the faster we're carried, the less time we have to spare. During the earlier years of this period, while bangs and bustles were having their way with women, there were seen men of all ages to whom a hat meant only that rigid, tall silk thing known to impudence as a stovepipe. But the long contagion of the derby had arrived. One season the crown of this hat would be a bucket; the next it would be a spoon. Every house still kept its bootjack, but high-top boots gave way to shoes and congress gaiters, and these were played through fashions that shaped them now with toes like box ends, and now with toes like the prows of racing shells. Trousers with a crease were considered plebian; the crease proved that the garment had lain upon a shelf and hence was ready-made. With evening dress, a gentleman wore a tan overcoat, so short that his black coattails hung visible five inches below the overcoat. But after a season or two, he lengthened his overcoat till it touched his heels. And he passed out of his tight trousers into trousers like great bags. In those days, they had time for everything. Time for sleigh rides, and balls, and assemblies, and cotillions, and open house on New Year's, and all-day picnics in the woods, and even that prettiest of all vanished customs: the serenade. Of a summer night, young men would bring an orchestra under a pretty girl's window, and flute, harp, fiddle, cello, cornet, bass viol, would presently release their melodies to the dulcet stars. Against so home-spun a background, the magnificence of the Ambersons was as conspicuous as a brass band at a funeral.

-

George: I said, automobiles are a useless nuisance. Never amount to anything but a nuisance. They had no business to be invented.

-

Maj. Amberson: So your devilish machines are going to ruin all your old friend, eh Gene? Do you really think they're going to change the face of the land?

Eugene: They're already doing it major and it can't be stopped. Automobiles...

[cut off by George]

George: Automobiles are a useless nuisance.

Maj. Amberson: What did you say George?

George: I said automobiles are a useless nuisance. Never amount to anything but a nuisance and they had no business to be invented.

Jack: Of course you forget that Mr. Morgan makes them, also did his share in inventing them. If you weren't so thoughtless, he might think you were rather offensive.

Eugene: I'm not sure George is wrong about automobiles. With all their speed forward they may be a step backward in civilization. May be that they won't add to the beauty of the world or the life of the men's souls, I'm not sure. But automobiles have come and almost all outwards things will be different because of what they bring. They're going to alter war and they're going to alter peace. And I think men's minds are going to be changed in subtle ways because of automobiles. And it may be that George is right. May be that in ten to twenty years from now that if we can see the inward change in men by that time, I shouldn't be able to defend the gasoline engine but agree with George - that automobiles had no business to be invented.

-

[last lines]

Eugene: Fanny, I wish you could have seen Georgie's face when he saw Lucy. You know what he said to me when we went into that room? He said, "You must have known my mother wanted you to come here today, so that I could ask you to forgive me." We shook hands. I never noticed before how much like Isabel Georgie looks. You know something, Fanny? I wouldn't tell this to anybody but you. But it seemed to me as if someone else was in that room. And that through me, she brought her boy unto shelter again. And that I'd been true at last, to my true love.

-

Roger Bronson: [to George] The law's a jealous mistress and a stern mistress.

-

Narrator: George Amberson-Minafer walked home through the strange streets of what seemed to be a strange city. For the town was growing... changing... it was heaving up in the middle, incredibly; it was spreading incredibly. And as it heaved and spread, it befouled itself and darkened its skies. This was the last walk home he was ever to take up National Avenue, to Amberson Edition, and the big old house at the foot of Amberson Boulevard. Tommorow they were to move out. Tomorrow everything would be gone.

-

Maj. Amberson: There must be the Sun. There wasn't anything here. The Sun in the first place. Sun. The earth came out of the Sun. We came out of the earth. So, whatever we are... it must have been the earth...

-

Citizen: Wilbur Minafer. Quiet man. Town'll hardly know he's gone.

-

Jack: My gosh, the old times are certainly starting all over again.

Eugene: Old times, not a bit. There aren't any old times. When times are gone, they're not old, they're dead. There aren't any times but new times.

-

Lucy: Who's that?

George: Oh, I didn't catch his name when my mother presented him to me. You mean the queer looking duck?

Lucy: The who?

George: The queer looking duck.

-

George: How'd all these ducks get to know you so quick?

Lucy: Oh, I've been here a week.

George: Seems to me you've been pretty busy.

-

George: Anybody that really is anybody ought to be able to do about as they like in their own town, I should think.

-

George: How is that for a bit of freshness?

Lucy: What was?

George: That queer looking duck waving his hand at me like that.

Lucy: He meant me!

George: Oh, he did? Everybody seems to mean you.

-

George: Most girls are usually pretty fresh. They ought to go to a man's college for about a year. They'd get taught a few things about freshness. Look here, who sent you those flowers you keep making such a fuss over?

-

George: [disparagingly] Horseless carriages. Auto-mobiles. People aren't going to spend their lives lying on their backs on the road letting grease drip in their face. No, I think you're father better forget about 'em.

Lucy: Papa will be so grateful if he could get your advice.

George: I don't know that I've done anything to be insulted for.

Lucy: You know, I don't mind you being such a lofty person, at all. I think its ever so interesting. But, Papa's a great man.

-

Lucy: How lovely your mother is.

George: I think she is.

Lucy: She's the gracefullest woman. She dances like a girl of 16.

George: Most girls of 16 are pretty bad dancers. Anyhow, I wouldn't dance with one of 'em unless I had to.

-

Fanny Minafer: I suppose your mother's been pretty gay at the Commencement.

-

Jack: Nobody has a good name in a bad mouth! Nobody has a good name in a silly mouth, either.

-

Eugene: I know what your son is to you and it frightens me. Let me explain a little. I don't think he'll change. At twenty-one or twenty-two, so many things appear solid and permanent and terrible. Which forty sees are nothing but disappearing miasma. Forty can't tell twenty about this. Twenty can find out only by getting to be forty.

-

Lucy: Don't you remember? We'd had a quarrel and we didn't speak to each other all the way home from a long, long drive. And since we couldn't play together like good children, of course, it was plain we oughtn't of play at all.

George: Play?

Lucy: What I mean is, we've come to the point where it was time to quite playing. Well, what we were playing.

George: That being love, as you mean, don't you?

Lucy: Something like that. It was absurd.

-

Narrator: And now, Maj. Amberson was engaged in the profoundest thinking of his life. And he realized that everything which had worried him or delighted him during this lifetime, all his buying and building and trading and banking, that it was all trifling and waste - beside what concerned him now. For the Maj. knew now that he had to plan how to enter an unknown country, where he was not even sure of being recognized as an Amberson.

-

Jack: You can't ever tell what will happen at all, can you? Once I stood where we're standing now to say goodbye to a pretty girl. Only, it was in the old station, before this was built. We called it the depot. We knew we wouldn't see each other again for almost a year. I thought I couldn't live through it. She stood there crying. Don't even know where she lives now. If she is living.

-

Jack: Life and money both behave like - loose quicksilver in a nest of cracks. When they're gone, you can't tell where or what the devil you did with them.

The Magnificent Ambersons Quotes

-

Christina 2022-03-23 09:03:27

Looking at you is like seeing through my bleakness

-

Clifford 2022-03-27 09:01:21

Very unwelcome film, didactic and happy ending. There are only a few scenes where the camera movement shows Wells' soul. In addition, is this 88-minute version messed up? The rhythm is very jumpy.

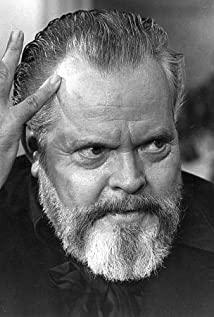

Director: Orson Welles, Robert Wise

Language: English Release date: July 10, 1942