-

Dr. Alice Howland: Hi, Alice. I'm you. And I have something very important to say to you. Huh... I guess you've reached that point when you can answer any of your questions. So this is the next logical step. I'm sure of it. Because what's happening to you, the Alzheimer's - you could see it as tragic. But your life has been anything but tragic. You've had a remarkable career, and a great marriage, and three beautiful children. All right. Listen to me, Alice. This is important. Make sure that you are alone and go to the bedroom. In your bedroom, there's a dresser with a blue lamp. Open the top drawer. In the back of the drawer, there's a bottle with pills in it. It says 'take all pills with water'. Now, there are a lot of pills in that bottle, but it's very important that you swallow them all, okay? And then, lie down and go to sleep. And don't tell anyone what you're doing, okay?

-

Dr. Alice Howland: Good morning. It's an honor to be here. The poet Elizabeth Bishoponce wrote: 'the Art of Losing isn't hard to master: so many things seem filled with the intent to be lost that their loss is no disaster.' I'm not a poet, I am a person living with Early Onset Alzheimer's, and as that person I find myself learning the art of losing every day. Losing my bearings, losing objects, losing sleep, but mostly losing memories...

[she knocks the pages from the podium]

Dr. Alice Howland: I think I'll try to forget that just happened.

[crowd laughs]

Dr. Alice Howland: All my life I've accumulated memories - they've become, in a way, my most precious possessions. The night I met my husband, the first time I held my textbook in my hands. Having children, making friends, traveling the world. Everything I accumulated in life, everything I've worked so hard for - now all that is being ripped away. As you can imagine, or as you know, this is hell. But it gets worse. Who can take us seriously when we are so far from who we once were? Our strange behavior and fumbled sentences change other's perception of us and our perception of ourselves. We become ridiculous, incapable, comic. But this is not who we are, this is our disease. And like any disease it has a cause, it has a progression, and it could have a cure. My greatest wish is that my children, our children - the next generation - do not have to face what I am facing. But for the time being, I'm still alive. I know I'm alive. I have people I love dearly. I have things I want to do with my life. I rail against myself for not being able to remember things - but I still have moments in the day of pure happiness and joy. And please do not think that I am suffering. I am not suffering. I am struggling. Struggling to be part of things, to stay connected to whom I was once. So, 'live in the moment' I tell myself. It's really all I can do, live in the moment. And not beat myself up too much... and not beat myself up too much for mastering the art of losing. One thing I will try to hold onto though is the memory of speaking here today. It will go, I know it will. It may be gone by tomorrow. But it means so much to be talking here, today, like my old ambitious self who was so fascinated by communication. Thank you for this opportunity. It means the world to me. Thank you.

-

Dr. Alice Howland: I was looking for this last night.

Dr. John Howland: [whispering to Anna] It was a month ago.

-

Dr. Alice Howland: Help me find my phone.

-

Lydia Howland: But this isn't fair.

Dr. Alice Howland: I don't have to be fair. I'm your mother.

-

Dr. Alice Howland: I used to be someone who knew a lot. No one asks for my opinion or advice anymore. I miss that. I used to be curious and independent and confident. I miss being sure of things. There's no peace in being unsure of everything all the time. I miss doing everything easily. I miss being a part of what's happening. I miss feeling wanted. I miss my life and my family.

-

Dr. Alice Howland: You may say that this falls into the great academic tradition of knowing more and more about less and less until we know everything about nothing.

-

Dr. Alice Howland: I need something to read.

Dr. John Howland: I thought you were reading Moby Dick.

Dr. Alice Howland: Yeah, I was. But I got tired of reading the same page over and over again. I can't focus.

Dr. John Howland: Well, that happens to me when I read Moby Dick too.

-

Dr. Alice Howland: When I was, um, a little girl, like, in second grade, my teacher told me butterflies don't live a long time. They live, like, a month. And I was so upset, and I went home, and I told my mother, and she said: "Yeah, but, you know, they have a nice life. They have a really beautiful life." So now it always makes me think about my mother's life, and my sister's life. And to a certain extent, you know, my own.

-

Lydia Howland: You can't use your situation to just get me to do everything you want me to do.

Dr. Alice Howland: Why can't I?

Lydia Howland: Because that's not fair.

Dr. Alice Howland: I don't have to be fair. I'm your mother.

-

[last lines]

Lydia Howland: [reading to her mother, but mostly from memory] "Night flight to San Francisco chase the moon across America. God, it's been years since I was on a plane. When we hit 35,000 feet, we'll have reached the tropopause, the great elt of calm air. As close to the ozone as I'll get, I - I dreamed we were there. The plane leapt the tropopause, the safe air, and attained the outer rim, the ozone, which was ragged and torn, patches of it threadbare as old cheesecloth, and that was... frightening."

Lydia Howland: "But I saw something only I could see because of my astonishing ability to see such things. Souls were rising, from the earth far below, souls of the dead, of people who's perished from famine, from war, from the plague... And they floated up, like skydivers in reverse, limbs all akimbo, wheeling, spinning. And the souls of these departed joined hands, clasped ankles and formed a web, a great net of souls. And the souls were three-atom oxygen molecules of the stuff of ozone and the outer rim absorbed them, and was repaired. Because nothing is lost forever. In this world, there a kind of painful progress. A longing for what we've left behind, and dreaming ahead. At least I think that's so."

Lydia Howland: [moving over alongside her mother] Hey. Did you like that. What I jest read, did you like it?

Dr. Alice Howland: [barely grunting]

Lydia Howland: And what... What was it about?

Dr. Alice Howland: Love. Yeah, love.

Lydia Howland: Yeah, it was about love.

-

Dr. John Howland: I think it's ridiculous, I think it's bullshit, and I...

Dr. Alice Howland: Damn it, why won't you take me seriously? Look, I KNOW what I'm feeling, and I... I feel, I feel like my brain is... is fucking DYING and everything I know and everything I worked for, it's all going...

[bursts into terrified sobbing]

-

Dr. Alice Howland: [Alice has peed herself after forgetting where the bathroom is in her own home] ... I couldn't find the bathroom.

Dr. John Howland: ...It's okay baby, we'll... we'll get you cleaned up...

Dr. Alice Howland: [sobbing in a panic] I don't know where I am!

-

Dr. Alice Howland: [John has discovered Alice's missing phone in the kitchen freezer] ... Oh no! I was looking for that last night!

Dr. John Howland: [whispers to Anna] That was a month ago.

-

Dr. John Howland: Why don't you wear a fanny pack, is it really THAT inhibiting?

-

Dr. Alice Howland: [regarding the newborn twins] Can I hold one?

Charlie Howland-Jones: [to Anna] Uh... do you, do you think that's a good idea?

Dr. Alice Howland: I know how to hold a baby.

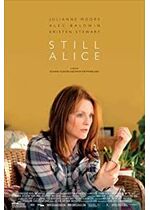

Still Alice Quotes

Extended Reading